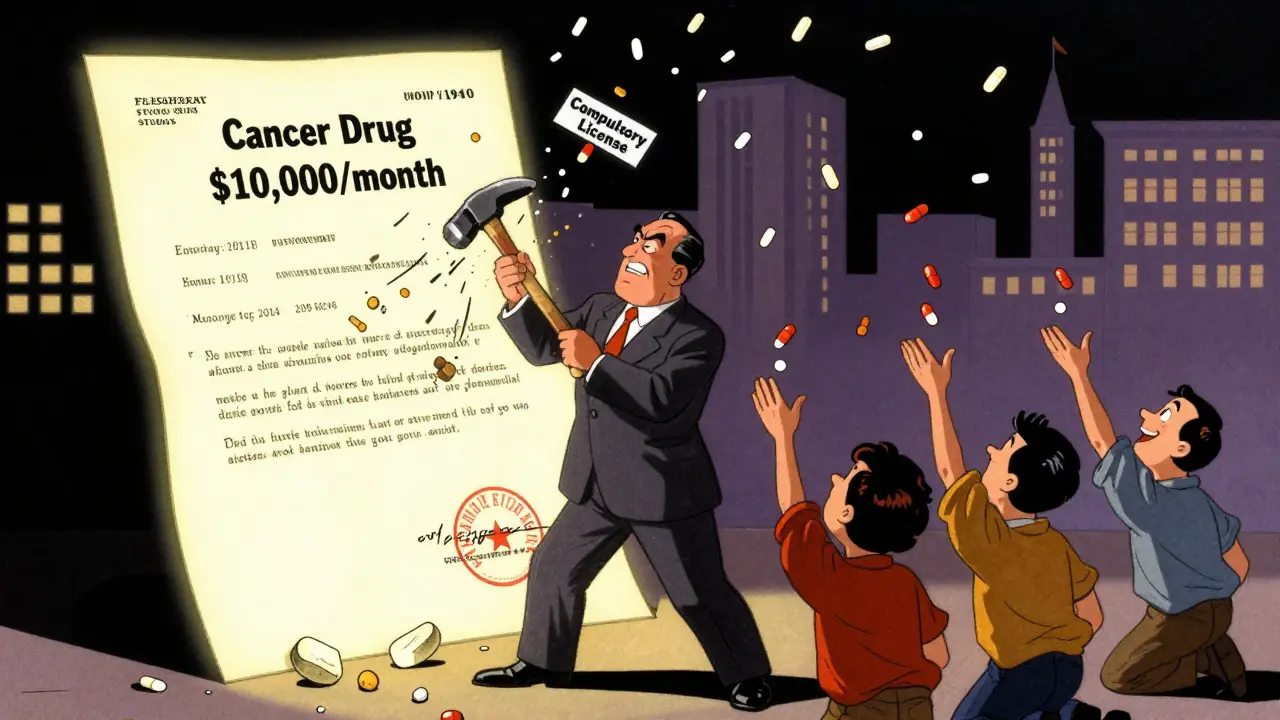

What compulsory licensing really means

Compulsory licensing isn’t about stealing patents. It’s about letting someone else make a drug - even without the company’s permission - when lives are at stake. The patent holder still gets paid, but the government steps in to make sure the medicine is available, fast and affordable. This isn’t theoretical. It’s been used in real emergencies, from HIV outbreaks to COVID-19, to stop people from dying because a drug was too expensive.

Think of it like this: a company holds a patent on a life-saving cancer drug that costs $10,000 a month. Only a few thousand people can afford it. Meanwhile, tens of thousands are waiting. Compulsory licensing lets a local manufacturer produce a generic version for $500 a month. The original company still gets a fair royalty - usually a percentage of sales - but now the drug reaches people who otherwise wouldn’t have access.

How it works under international law

The global rulebook for this is the TRIPS Agreement, part of the World Trade Organization’s framework from 1994. Article 31 says governments can issue compulsory licenses, but only under strict conditions. First, they must try to negotiate with the patent holder first. That’s the default rule. But if there’s a public health emergency - like a pandemic, a sudden disease outbreak, or a national crisis - that step can be skipped. Speed matters more than paperwork.

There’s another key rule: the license must be mostly for the country’s own use. You can’t just issue a license to make drugs for export unless you’re a country with no manufacturing capacity. That’s why the WTO created a special waiver in 2003 - later made permanent in 2005 - to let poor countries import medicines made under compulsory license from countries that can produce them. Canada used this once, in 2012, to send HIV drugs to Rwanda.

Where it’s actually been used

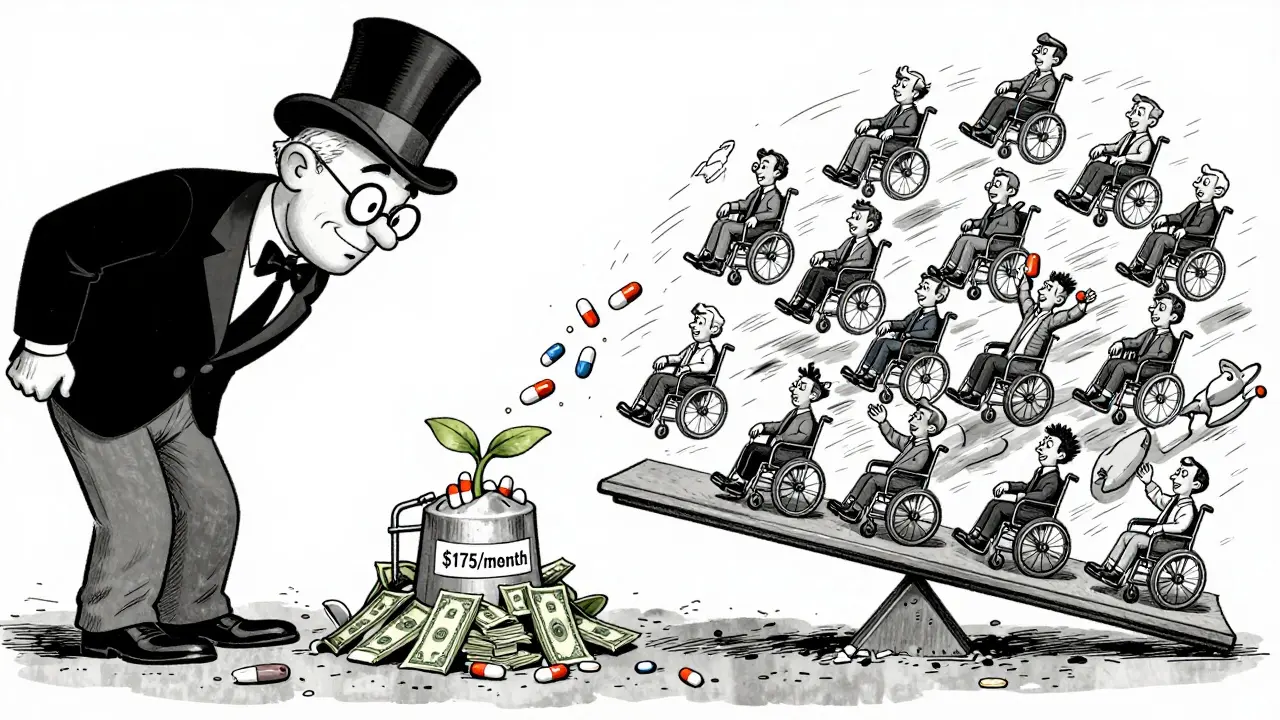

India leads the world in compulsory licensing for medicines. Since 2005, it’s issued 22 licenses, mostly for cancer drugs. The most famous case was in 2012, when India allowed Natco Pharma to make a generic version of Bayer’s kidney cancer drug Nexavar. The price dropped from $5,500 per patient per month to just $175. Bayer sued. The case dragged on for eight years. India stood by its decision. Patients lived.

Thailand did something similar in the mid-2000s. It issued licenses for HIV and heart drugs, cutting prices by up to 90%. Abbott’s lopinavir/ritonavir went from $1,200 a year to $230. Bristol-Myers Squibb’s efavirenz dropped from $550 to $200. The Thai government didn’t wait for negotiations. They acted fast, and thousands got treatment.

Brazil used compulsory licensing for HIV drugs too. In 2007, it forced Merck to lower the price of efavirenz from $1.55 per tablet to $0.48. The result? More people on treatment, fewer deaths, lower long-term healthcare costs.

How the U.S. handles it - and why it rarely happens

The U.S. has three legal paths for compulsory licensing, but none of them are easy. The most common is Section 1498 of Title 28. It lets the federal government use a patented invention - say, a vaccine or medical device - without the patent holder’s consent. But the company can sue for compensation in the Court of Federal Claims. The government doesn’t pay upfront. It pays after the fact. Between 1945 and 2020, only 10 licenses were issued under this rule - all for government use, never for public access.

Then there’s the Bayh-Dole Act. If a drug was developed with federal funding - say, through NIH grants - the government can force a license if the company isn’t making the drug available to the public. But here’s the catch: the NIH has received 12 petitions since 1980. It has never granted one. Why? Because they always claim the company is “taking effective steps.” Even when prices are sky-high, the bar is set too high to trigger action.

And then there’s the Clean Air Act, which lets the government license patented pollution-control tech. But that’s about emissions, not medicine. So for drugs? The U.S. rarely uses compulsory licensing. It relies on negotiation, market pressure, or just waiting.

The real impact: prices, access, and lives saved

The numbers don’t lie. Between 2000 and 2020, compulsory licensing helped cut the price of first-line HIV drugs by 92% in low- and middle-income countries. That’s not a small win. It’s the difference between life and death for millions.

Generic manufacturers like Teva saw their revenue from these markets jump by $3.2 billion between 2015 and 2020. But it’s not just about money. It’s about access. Before compulsory licenses, many African countries couldn’t afford even basic HIV treatment. After, treatment rates soared. In some places, HIV transmission dropped by half.

During the pandemic, 40 countries - including Germany, Canada, and Israel - prepared or issued licenses for COVID-19 treatments and vaccines. Some used emergency waivers. Others moved fast on existing laws. But the global response was slow. Only 12 facilities worldwide were authorized to produce vaccines under the WTO’s 2022 waiver - far below what was needed.

Why big pharma fights it - and what they get wrong

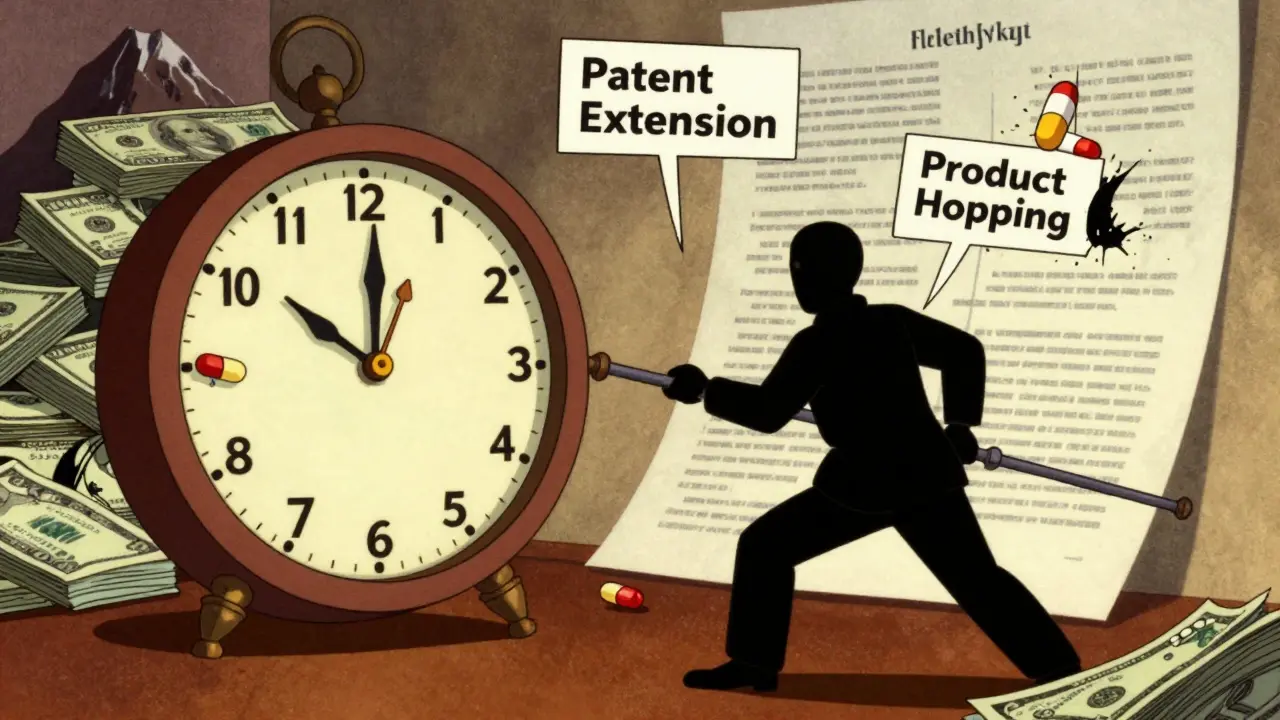

Pharmaceutical companies argue that compulsory licensing kills innovation. They say if you let governments override patents, no one will invest in new drugs. A 2018 study claimed R&D investment dropped 15-20% in countries with active licensing programs. But that’s misleading. The same study didn’t account for the fact that most new drugs are still developed in rich countries - where licensing is rare - and funded by public money anyway.

Dr. Brook Baker from Northeastern University points out something most people miss: the threat of compulsory licensing often works better than the license itself. Since 2000, 90% of HIV drugs in developing countries got price cuts without a license being issued. Just the possibility of one pushed companies to lower prices voluntarily.

And when a license is issued, it doesn’t kill innovation. It redirects it. Companies still invest in new molecules - but they also start thinking about pricing and access from day one. They know: if you charge $1 million per dose, someone will find a way to make it cheaper.

What’s changing now - and what’s next

Things are shifting. In 2023, the European Union proposed a new pharmaceutical strategy that forces patent holders to offer licensing terms within 30 days - or risk an automatic compulsory license. That’s a game-changer. It flips the script: instead of governments chasing companies, companies now have to come to the table fast.

The WHO is also drafting a Pandemic Treaty. One draft article says that during a declared global health emergency, essential health products should be automatically licensed. No negotiations. No delays. That could mean the next pandemic doesn’t leave millions behind because of patent walls.

And the numbers are growing. The Boston Consulting Group predicts a 40% rise in compulsory licensing activity between 2023 and 2028 - driven by antimicrobial resistance, climate-related health threats, and aging populations.

What you need to know if you’re affected

If you’re a patient struggling to afford a patented drug, compulsory licensing might be your only path to treatment. But you can’t file one yourself. It’s a government tool. That means your best move is to advocate. Talk to your local health officials. Push your representatives. Share stories. Demand transparency.

If you’re a researcher or public health worker, understand your country’s patent laws. Know what’s possible. In India, you need to prove public need and that you can make the drug. In Canada, you need an emergency declaration. In Brazil, you need to show the drug is priced beyond reach. Each country has its own rules - but the goal is the same: save lives, not protect profits.

Common myths about compulsory licensing

- Myth: It’s theft. Truth: It’s legal under international law. The patent holder is paid.

- Myth: It stops innovation. Truth: Most new drugs are still developed in countries that rarely use compulsory licenses.

- Myth: Only poor countries use it. Truth: Germany, Canada, and the U.S. have the legal power - they just rarely use it.

- Myth: It’s too slow. Truth: In emergencies, the negotiation step is waived. Thailand and Brazil acted in weeks.

Final thoughts

Compulsory licensing isn’t about being anti-patent. It’s about being pro-life. Patents exist to encourage innovation - not to block access. When a drug costs more than a person’s annual income, the system has failed. Compulsory licensing is the reset button. It’s not perfect. It’s not easy. But when used right, it saves more lives than any legal loophole ever could.

Paige Shipe

Compulsory licensing is a slippery slope. Once you start overriding patents, where do you draw the line? Next thing you know, someone’s making knockoff iPhones because they can’t afford the latest model. This isn’t healthcare policy-it’s economic sabotage dressed up as morality.

Tamar Dunlop

I find it profoundly moving that nations like India and Thailand chose humanity over corporate profit margins. To witness a government prioritize the dignity of its citizens over the balance sheets of multinational conglomerates-this is not merely policy. It is an act of moral courage that echoes across generations. The world needs more of this.

David Chase

USA. WE. DON’T. NEED. THIS. 🇺🇸 We fund 80% of global pharma R&D. Without us, none of these drugs exist. So yeah, if you’re a poor country and you can’t afford the price tag? That’s YOUR problem. Not ours. Stop stealing our innovation. #PatentsAreProperty #MakeAmericaInnovateAgain

Emma Duquemin

Let me tell you what really happened in India after the Nexavar license-people who were literally dying on hospital floors got to go home. Not because they were lucky. Not because they begged. Because someone in a government office had the guts to say, 'Enough.' I’ve seen families cry over a $175 pill that saved their father. That’s not economics. That’s redemption. And if Big Pharma cries? Good. Let them cry while people breathe.

Kevin Lopez

TRIPS Article 31 is non-negotiable. Compulsory licensing requires prior negotiation. Thailand skipped it. Brazil skipped it. That’s a violation. The WTO waiver for exports is a loophole. It’s not a solution. And the 90% price drop? That’s not access-it’s price suppression. You can’t sustain innovation on charity.

Duncan Careless

I’ve worked in public health for over two decades. What I’ve seen in rural clinics isn’t theory-it’s children waiting for antiretrovirals because their parents can’t afford a single month’s supply. Compulsory licensing isn’t radical. It’s the bare minimum. The fact that we even debate this shows how far we’ve drifted from what medicine is supposed to be.

Samar Khan

India gave us the world’s generic pharmacy. But now? The same companies that cried foul when Natco made Nexavar are now licensing their own tech to China. Hypocrisy much? 🤦♀️ We didn’t steal. We outsmarted. And if you think that’s wrong, you’ve never watched someone die because a pill cost more than their rent.

Russell Thomas

Oh wow, so now we’re supposed to feel bad because a company made a drug and then charged what the market would bear? Maybe if people stopped expecting free stuff, they’d stop being so shocked when capitalism doesn’t hand out freebies. Also, who’s paying for the R&D? The poor? The government? The aliens?

Joe Kwon

The data shows that compulsory licensing doesn’t reduce innovation-it redirects it. Companies start designing for affordability from day one. Look at the mRNA vaccines: they were built with public funding, and now we’re seeing tiered pricing models because of pressure from global access advocates. This isn’t an attack on IP. It’s an evolution of it.

Nicole K.

This is just socialism with a fancy name. If you can’t afford medicine, get a better job. Or don’t get sick. Simple as that. People who think the government should pay for their drugs are just lazy and entitled.

Fabian Riewe

I used to think patents were sacred. Then I met a guy in Ohio who had to choose between his insulin and his rent. He picked rent. He died three weeks later. That’s not capitalism. That’s failure. Compulsory licensing isn’t about punishing companies-it’s about fixing a system that lets people die because of a spreadsheet.

Greg Quinn

There’s a deeper question here: what does it mean to own knowledge? A patent is a monopoly granted by the state-not a natural right. If the state grants it to encourage innovation, then it also has the moral authority to revoke it when that innovation becomes a weapon of exclusion. The real crime isn’t licensing-it’s pretending that profit should always trump survival.

Lisa Dore

To anyone who says this kills innovation: show me the last breakthrough drug that came from a country that *never* used compulsory licensing. Hint: it’s not happening. The real innovation is happening in labs funded by NIH, Gates Foundation, and public universities. The patent is just the tax on the result-not the source.

Sharleen Luciano

Let’s be honest-this is just a thinly veiled attempt to redistribute wealth under the guise of public health. If you want cheap drugs, move to a country that doesn’t have a patent system. Or better yet, stop having expensive diseases. The rest of us have to pay for your choices.