Immunocompromised Infection Risk Calculator

Assess Your Infection Risk

This tool helps you understand your personal infection risk based on your medications and other factors. Remember: immunocompromised patients have a higher risk of serious infections that may not show typical symptoms like fever or redness.

Your Medications

When your immune system is weakened-whether from cancer treatment, an organ transplant, or an autoimmune disease like rheumatoid arthritis or lupus-taking medication becomes a high-stakes balancing act. What helps control your condition might also leave you dangerously exposed to infections that could land you in the hospital. This isn’t theoretical. People on immunosuppressants are 1.6 times more likely to develop serious infections than those not on these drugs, according to a major 2012 study of over 4,000 patients. And for many, the signs of infection don’t look the way they should.

What Does It Mean to Be Immunocompromised?

Being immunocompromised means your body’s defense system isn’t working the way it should. You might not run a fever when you’re sick. Your cough might not get worse. Your skin might not swell or turn red. That doesn’t mean you’re not infected-it means your immune system can’t mount the usual response. This happens for a few reasons: you could have a disease like HIV or leukemia, you might be on long-term steroids like prednisone, or you’ve had a transplant and need drugs to stop your body from rejecting the new organ. The problem isn’t just getting sick. It’s that you get sicker, faster. And the usual red flags-fever, chills, swelling-might not show up at all. Dr. Francisco Aberra and Dr. David Lichtenstein found that corticosteroids, in particular, can mask the classic signs of infection. So a patient might feel tired, have a slight cough, and assume it’s just stress. Weeks later, they’re in the ICU with pneumonia that went unnoticed.How Different Medications Raise Different Risks

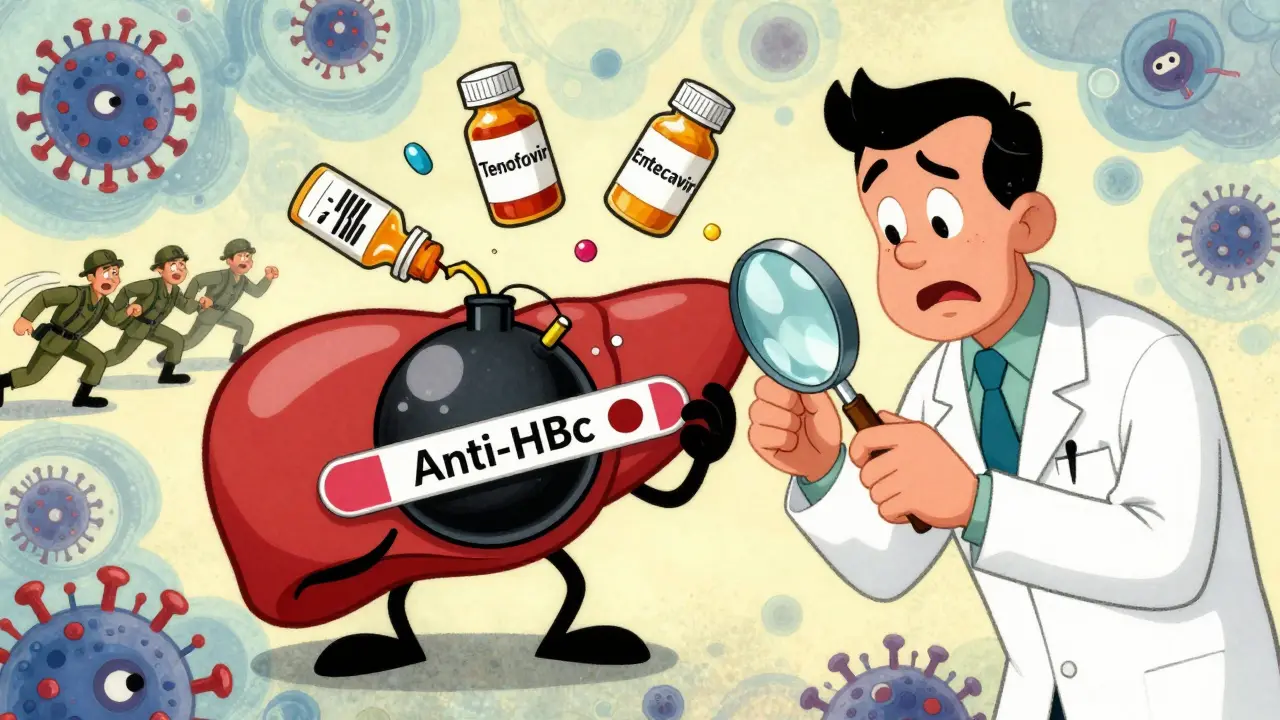

Not all immunosuppressants are the same. Each class shuts down parts of the immune system in different ways, and each carries its own set of dangers.Corticosteroids like prednisone, dexamethasone, and methylprednisolone are among the most common. They’re cheap, fast-acting, and effective for inflammation. But they’re also the most dangerous when used long-term. At doses higher than 20mg of prednisone daily for more than two weeks, infection risk jumps sharply. A 2012 meta-analysis showed 12.7% of steroid users developed infections compared to just 8% in control groups. The risk isn’t just bacterial-it’s fungal, viral, and even reactivated old viruses like shingles (herpes zoster) or hepatitis B.

Methotrexate, a conventional DMARD used for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, affects about half of users with side effects: nausea, fatigue, mouth sores, and liver stress. Nearly 70% say it controls their disease well, but nearly half quit within a year because the side effects are too much. Blood tests every month are required to catch liver damage or low white blood cell counts before they become dangerous.

Azathioprine reduces the number of T and B cells, which are key fighters in your immune system. The biggest danger? Leukopenia-low white blood cells. That’s when you’re most vulnerable to bacterial infections, Pneumocystis pneumonia, and even a rare brain infection called PML caused by the JC virus. Patients on azathioprine are also at higher risk for hepatitis B and C flare-ups.

Biologics-like Humira, Enbrel, or Remicade-are the most powerful. They target specific parts of the immune system, like TNF-alpha, to stop inflammation. But that precision comes at a cost: they’re linked to the highest rates of serious infections among all immunosuppressants. Many patients on Reddit’s r/RheumatoidArthritis forums report hospitalizations after developing shingles or pneumonia while on these drugs. One user described waking up with a rash that looked like sunburn-only to find out it was herpes zoster spreading across their chest.

Cyclosporine and tacrolimus, used mostly after transplants, carry risks of viral reactivation-especially Epstein-Barr virus (linked to lymphoma) and polyomavirus (which can damage kidneys). Patients often describe these drugs as “life-changing” but also “a constant shadow.” One kidney transplant recipient said, “I’m alive because of tacrolimus. But I check every cough like it’s my last.”

Chemotherapy drugs like cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel are the most aggressive. They don’t just target cancer-they wipe out fast-dividing cells, including immune cells. Patients on chemo are often told to avoid crowds, wear masks, and skip flu shots during treatment. Their infection risk is higher than almost any other group on immunosuppressants.

Combining Drugs Makes Things Worse

Taking two or more immunosuppressants together doesn’t just add risk-it multiplies it. A steroid plus methotrexate? Higher chance of pneumonia. A biologic plus azathioprine? Risk of PML jumps. The PMC article on infections in immunocompromised hosts calls this “synergistic immunosuppression.” It’s not just the sum of the parts. It’s the interaction that’s deadly.That’s why doctors are moving away from triple therapy unless absolutely necessary. Many now start with one drug, monitor closely, and only add another if the first fails. The goal isn’t to suppress every last bit of immune activity-it’s to control the disease while leaving enough defense to fight off everyday germs.

How Infections Hide-and Why They’re So Dangerous

One of the biggest traps for immunocompromised patients is that infections don’t act like they do in healthy people. You might not have a fever. Your lungs might be filling with fluid, but you don’t feel short of breath until it’s too late. Your skin might be pale, not red. Your gut might be bloated, but not painful.That’s why patients on steroids are often told: “If you feel off, even a little, get checked.” A low-grade temperature of 99.5°F might be your body’s only signal. A headache and fatigue could mean meningitis. A cough that won’t go away could be tuberculosis. These aren’t rare scenarios-they happen weekly in clinics that treat transplant and autoimmune patients.

The CDC warns that vector-borne diseases-like Lyme disease from ticks or West Nile from mosquitoes-are especially dangerous for this group. A healthy person might get a rash and a fever and recover. An immunocompromised person might develop sepsis or brain inflammation.

What You Can Do to Protect Yourself

There’s no magic shield-but there are proven steps that cut infection risk dramatically.- Wash your hands for 20 seconds-long enough to sing “Happy Birthday” twice. Pay attention to under your nails and between your fingers. Use alcohol-based sanitizer when soap isn’t available.

- Wear a mask in crowded places, especially during flu season or in hospitals. N95s or KN95s are better than cloth masks.

- Get vaccinated-but only the right ones. Flu shots, pneumococcal vaccines, and Hepatitis B vaccines are safe and recommended. Live vaccines (like MMR or shingles vaccine) are usually off-limits unless your immune system is stable.

- Check your skin daily. Look for new rashes, sores, or unusual swelling. Even a small cut can turn into a serious infection.

- Know your baseline. Keep a log of your normal energy levels, appetite, and sleep. When you feel “off,” compare it to your baseline. That’s often the first clue something’s wrong.

Many patients also keep a “red flag” list with their doctor: fever over 100.4°F, new cough, unexplained fatigue, diarrhea lasting more than 2 days, or a rash that spreads. If any of these show up, they call their provider immediately-no waiting.

What the Latest Research Tells Us

In 2021, Johns Hopkins published a surprising finding: people on immunosuppressants didn’t have worse outcomes from COVID-19 than the general population. In fact, some had milder cases. That flipped the script. For years, everyone assumed immunosuppression meant higher death risk from viruses. Turns out, it’s more complex. Maybe suppressing the immune system prevented the dangerous “cytokine storm” that kills some COVID patients.That doesn’t mean you can ignore the risk. It means your risk profile is personal. Your doctor needs to look at your specific drugs, your age, your other health conditions, and your lifestyle. One-size-fits-all advice doesn’t work here.

Researchers are now working on smarter drugs. JAK inhibitors like Xeljanz target only certain immune pathways, potentially reducing broad suppression. Pharmacogenomics-the study of how your genes affect how you respond to drugs-might one day let doctors tailor doses to your body, not just your disease.

The Emotional Weight of Living with Risk

Behind every statistic is a person. A mother who stopped going to her daughter’s school plays because she’s scared of germs. A man who cries when he sees a flu shot advertisement because he remembers his brother dying from pneumonia on methotrexate. A teenager who hides her rash because she doesn’t want to miss another day of school.Patients often say the hardest part isn’t the nausea or the fatigue-it’s the loneliness. No one else gets why you won’t go to a concert. Why you refuse to eat at buffets. Why you’re always the one asking, “Did anyone here get sick?”

But there’s hope too. Many patients report that with careful management, they’re living full lives. One transplant recipient said, “I’m 62. I travel, I garden, I dance with my grandkids. I just don’t go to crowded malls in winter.”

It’s not about avoiding life. It’s about knowing the rules-and playing smart.

Monitoring and Testing: What Your Doctor Should Be Checking

Regular blood tests aren’t optional-they’re lifesaving. Here’s what’s typically monitored:- Complete Blood Count (CBC)-every 1-4 weeks, especially when starting or changing meds. Looks for low white cells, low platelets.

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs)-methotrexate and leflunomide can damage the liver. Monthly checks are standard.

- Kidney Function-cyclosporine and tacrolimus are hard on kidneys. Creatinine and eGFR tracked regularly.

- Viral Panels-for patients on biologics or transplant drugs, tests for CMV, EBV, and hepatitis B/C are routine.

Some clinics now use risk prediction tools that combine lab results, drug doses, and patient history to estimate infection risk over the next 3 months. It’s not perfect-but it’s better than guessing.

Can I still get vaccines if I’m immunocompromised?

Yes-but only inactivated or non-live vaccines. Flu shots, pneumococcal vaccines, Hepatitis B, and COVID-19 boosters are safe and recommended. Live vaccines like MMR, varicella (chickenpox), and the old shingles vaccine (Zostavax) are usually avoided because they contain weakened viruses that could cause illness. The newer shingles vaccine, Shingrix, is non-live and safe for most immunocompromised patients. Always check with your doctor before getting any vaccine.

Do immunosuppressants cause cancer?

Some do, and that’s why many carry FDA black box warnings. Long-term use of drugs like azathioprine and cyclosporine increases the risk of skin cancer and lymphoma. This is why patients are advised to do monthly skin checks and avoid excessive sun exposure. The risk is small but real-especially if you’ve been on these drugs for over 10 years. Regular dermatology checkups are part of standard care for many transplant and autoimmune patients.

Why do I feel so tired on methotrexate?

Methotrexate interferes with folic acid, which your body needs to make new cells-including red blood cells. That’s why fatigue is so common. Many doctors prescribe folic acid supplements (1mg daily) to reduce this side effect. Taking it the day after your methotrexate dose helps. Some patients also report better energy after switching to subcutaneous injections instead of pills.

Can I travel while on immunosuppressants?

You can-but you need to plan. Avoid areas with high rates of malaria, dengue, or tuberculosis. Get travel-specific vaccines (non-live ones) at least 4 weeks before departure. Carry a letter from your doctor listing your medications and diagnosis. Bring extra doses in case of delays. Avoid raw foods, tap water, and street food in developing countries. Mosquito bites are a bigger threat than you think-use DEET repellent and sleep under nets if needed.

Is it safe to be around pets?

Yes, but with caution. Avoid cleaning litter boxes or bird cages-those can carry toxoplasmosis and psittacosis. Wash your hands after petting animals. Don’t let pets lick your face or open wounds. Reptiles and amphibians can carry salmonella-best avoided. Dogs and cats are generally fine if they’re healthy, vaccinated, and kept clean. Just be mindful of bites or scratches-even small ones can become infected.

What should I do if I think I’m getting sick?

Call your doctor immediately-don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s a cold. Even a mild fever, new cough, or unexplained fatigue could be something serious. Keep your medication list handy. If you’re in pain, confused, or breathing hard, go to the ER. Don’t wait for your regular appointment. Infections can turn deadly in 24 to 48 hours for immunocompromised patients.

Final Thoughts: Living With the Balance

Being immunocompromised isn’t a death sentence. It’s a new way of living-one that demands awareness, discipline, and communication. The medications that keep you alive also make you vulnerable. But with the right knowledge, monitoring, and habits, you can manage that risk without giving up your life.The goal isn’t to be fearless. It’s to be informed. To know your numbers. To recognize the quiet signs of trouble. To ask the hard questions. And to never feel alone in the fight.

Niamh Trihy

Just want to say this is one of the clearest, most practical guides I’ve read on immunosuppression. The breakdown of drug classes and their specific risks? Chef’s kiss. I’m a nurse in transplant oncology and I’ve seen too many patients miss the subtle signs-no fever, just fatigue-and end up in septic shock. That ‘if you feel off, get checked’ line? That’s gospel. Thank you for writing this.

KATHRYN JOHNSON

As a physician in Boston, I’ve seen the CDC’s data firsthand. The myth that immunocompromised patients always fare worse with infections is dangerously outdated. The 2021 Johns Hopkins finding on COVID-19 outcomes isn’t an anomaly-it’s a paradigm shift. We must stop treating all immunosuppression as equal. Precision medicine isn’t a buzzword here-it’s survival.

Kelly Weinhold

I’m a lupus patient on azathioprine and Humira. This post made me cry-not because I’m scared, but because someone finally got it. The loneliness? The ‘why won’t you come to dinner?’ guilt? The daily math of risk vs. joy? This isn’t just medical info-it’s a lifeline. I’ve shared it with my entire family. We’re all learning the rules now. Thank you for saying what we can’t always say out loud.

April Allen

The epistemological tension here is fascinating: we’re using pharmacological suppression to achieve homeostasis in autoimmune pathology, yet this very intervention destabilizes the host’s pathogen surveillance architecture. The JAK inhibitors represent a move toward modular immune modulation-reducing pleiotropic suppression while preserving sentinel functions. But we’re still in the dark ages of immune phenotyping. Until we can map individual immune resilience signatures, we’re just guessing with steroids and biologics.

Jason Xin

Yeah, and I’m sure the pharma reps loved this article. ‘Hey doc, here’s a 10-page essay on why your patient needs this $20k/year biologic.’ Meanwhile, my cousin on methotrexate just got shingles because his insurance denied the Shingrix vaccine. Real talk: access matters more than jargon. Not everyone has a Johns Hopkins doctor. Some of us just need to know if we can hug our grandkids without a hazmat suit.

Holly Robin

THIS IS ALL A LIE. The CDC is covering up the truth. Vaccines don't cause autism but they DO cause immune collapse. Look at the spike in PML cases after biologics got approved-coincidence? NO. Big Pharma is pushing these drugs because they make billions while people die quietly. They don't want you to know you can cure RA with turmeric and fasting. My cousin went off Humira and now she hikes every weekend. You're being manipulated. #WakeUp

Diksha Srivastava

Hey, I just wanted to say you’re not alone. I’ve been on prednisone for 8 years and I still feel like a ghost at parties. But guess what? I started a little garden last spring. I grow tomatoes, basil, marigolds. I talk to them like they’re my friends. And when I see the first ripe tomato? I cry. Not from sadness-from joy. You can still live. You just have to find your version of sunshine.

Adarsh Uttral

bro i got RA and on methotrexate. i dont even wash my hands that long anymore. i just use hand sanitizer and call it a day. also i eat street food in delhi like its nothing. i feel fine. maybe its all hype? 🤷♂️

Shawn Peck

Listen up. If you're on immunosuppressants and you're not getting checked every week, you're playing Russian roulette. I'm not being dramatic. I've seen three people die from a simple UTI because they waited too long. No excuses. No ‘I’m fine.’ If you're on these drugs, you're on borrowed time-and you better treat it like it.

Shubham Dixit

Let me tell you something about this ‘Western medicine’ nonsense. In India, we’ve been treating autoimmune conditions with Ayurveda for thousands of years. Turmeric, ashwagandha, guduchi-these aren’t supplements, they’re ancient science. Why are we blindly trusting patented drugs that cost a fortune and come with black box warnings? Our ancestors didn’t need biologics to live to 80. Modern doctors are selling fear, not solutions. I’ve seen patients in Delhi on methotrexate with full-blown infections-while their neighbors, on herbal regimens, are perfectly fine. This article reads like a Pfizer brochure. Wake up, people!

Yanaton Whittaker

IMMUNOCOMPROMISED = BAD. VACCINES = GOOD. MASKS = SMART. DOCTORS = TRUST THEM. 😊

Eliana Botelho

Okay but what if the real problem isn’t the drugs-it’s that we’re treating autoimmune diseases at all? Maybe your body isn’t ‘attacking itself’-maybe it’s trying to tell you something. Gluten, glyphosate, EMFs, chronic stress… that’s what’s wrecking your immune system. Drugs just cover it up. I went zero-waste, keto, and did a 21-day detox. My RA went away. No meds. No flares. No ‘risk.’ Just peace. Why won’t anyone talk about this?

Natasha Plebani

The existential burden here is profound: we are engineering biological compromise as a therapeutic strategy. We are trading immune vigilance for inflammatory quiescence-a Faustian bargain where the soul of the organism is negotiated away for temporary equilibrium. The irony is that the very systems designed to preserve life are the ones that render it perpetually precarious. We are not curing disease; we are negotiating its terms with death. And the contract is written in blood tests, not in wisdom.

Sheila Garfield

I’ve been on tacrolimus for 12 years post-kidney transplant. This article nailed it-the quiet fear, the checking every cough, the gratitude mixed with grief. I don’t have any grand advice. But I do know this: I still dance with my husband in the kitchen. I still cry at movies. I still plant flowers. I just don’t go to crowded concerts. And that’s okay. You don’t have to be brave to be alive. You just have to keep showing up.

Kathleen Riley

It is axiomatic that the pharmacological suppression of immune competence, while therapeutically efficacious in the context of autoimmune dysregulation, necessarily engenders a state of heightened vulnerability to exogenous pathogenic incursion. The epistemic imperative, therefore, lies not in the mere enumeration of risk factors, but in the ontological reconfiguration of patient agency within a biopolitical framework wherein medical authority is both indispensable and inherently paternalistic.