Every year, over 300,000 women die from cervical cancer worldwide. Most of these deaths aren’t inevitable-they’re preventable. The key lies in understanding HPV, how it causes cancer, and what we can do to stop it before it starts. This isn’t about fear. It’s about facts, tools, and choices that actually work.

What HPV Really Is-and Why It Matters

Human papillomavirus, or HPV, isn’t just one virus. It’s a family of more than 200 related viruses. About 40 of them affect the genital area. Most people will get at least one type of HPV in their lifetime. The good news? The body clears over 90% of these infections on its own within two years.

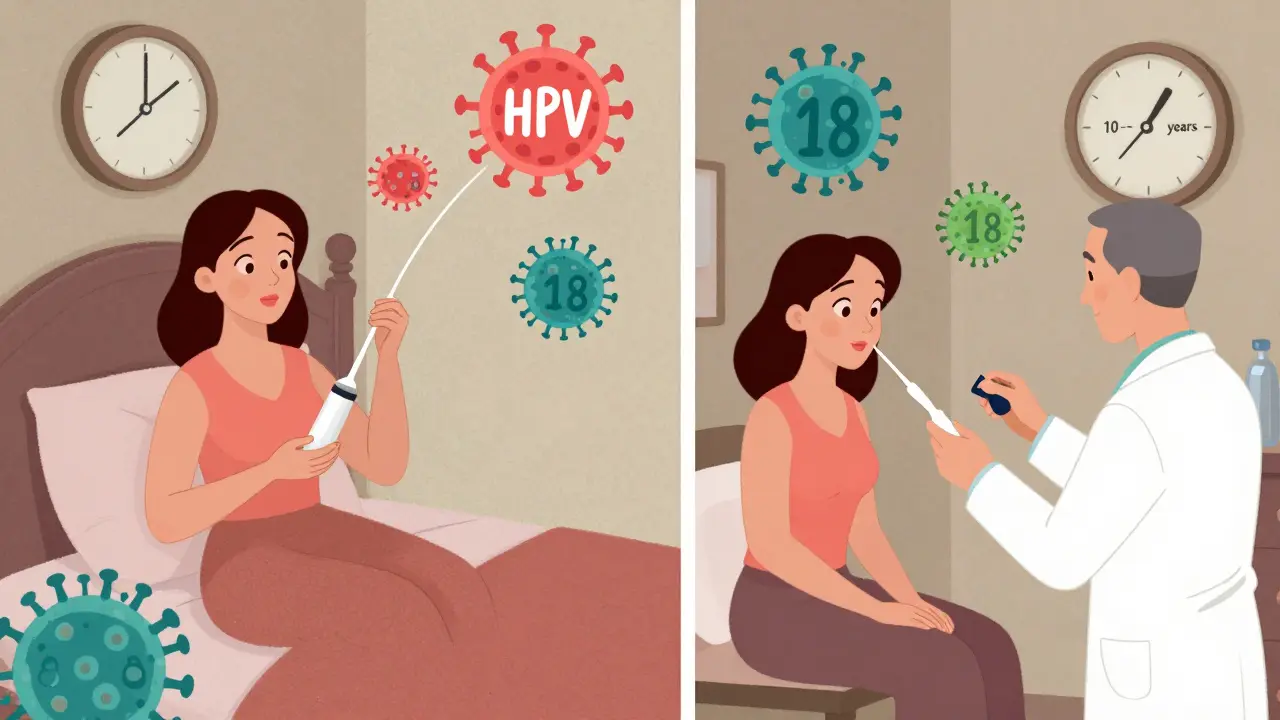

The problem comes with the high-risk types-especially HPV 16 and 18. These two alone cause about 70% of all cervical cancers. They don’t cause symptoms. You won’t feel them. You won’t know you have them unless you get tested. Left unchecked, they can slowly turn normal cervical cells into precancerous ones. That process takes 10 to 20 years. That’s not a fast-moving threat. It’s a slow-burning one-and that’s exactly why we have time to stop it.

Vaccination: The Best First Line of Defense

The HPV vaccine is one of the most effective cancer prevention tools ever developed. The first version, Gardasil, was approved in 2006. Today’s vaccines-like Gardasil 9-protect against nine types of HPV, including the two most dangerous: 16 and 18. They also cover types that cause genital warts.

It’s not just for teens. The CDC recommends vaccination for all kids at age 11 or 12. That’s when the immune response is strongest. But it’s still effective up to age 45. For people aged 15 to 26, three doses are needed. For those under 15, two doses are enough, spaced six months apart.

Real-world data shows the impact. In Australia, where vaccination rates are over 80% for girls and boys, cervical precancer rates in women under 25 have dropped by more than 85% since the vaccine rollout. In the U.S., HPV infections in teen girls fell by 88% between 2006 and 2018. These aren’t projections. They’re happening now.

And yes-you still need screening even if you’ve been vaccinated. The vaccine doesn’t cover every high-risk type. It prevents most, but not all. Screening is the safety net.

Screening: The Shift from Pap Tests to HPV Testing

For decades, the Pap smear was the gold standard. It looks at cervical cells under a microscope to spot abnormalities. It saved millions of lives. But it’s not perfect. It misses up to half of precancerous changes.

Today, we have something better: HPV testing. Instead of looking at cells, it checks for the virus itself-the root cause. Since 2020, the American Cancer Society has recommended primary HPV testing every five years for people aged 25 to 65. That’s the new standard.

Two tests are FDA-approved for this: the cobas HPV Test and the Aptima HPV Assay. Both detect 14 high-risk HPV types. The cobas test separates HPV 16 and 18 from the others. That’s important because if you test positive for one of those two, your risk of developing serious lesions is much higher. That changes how you’re followed up.

Why five years? Because HPV testing is more sensitive. A 2018 JAMA study found it detects 94.6% of precancers (CIN2+), compared to just 55.4% for Pap tests alone. And long-term data shows that after a negative HPV test, your risk of developing cancer in the next five years is extremely low-lower than after a negative Pap test.

For people aged 21 to 24, Pap tests are still recommended every three years. That’s because HPV is common in young adults, and most infections clear on their own. Testing too early can lead to unnecessary procedures.

What Happens If Your Test Is Positive?

A positive HPV test doesn’t mean you have cancer. It means the virus is present. Most of the time, nothing happens. But follow-up matters.

If you test positive for HPV 16 or 18, you’ll be referred for a colposcopy-a quick exam where a doctor looks at your cervix with a magnifying tool. A biopsy might be taken if anything looks unusual.

If you test positive for another high-risk type (not 16 or 18), you’ll usually get a Pap test at the same time. If the Pap is normal, you’ll be asked to come back in a year. If it’s abnormal, you’ll move to colposcopy.

This system-called reflex testing-is designed to avoid over-treatment. It finds the real threats and lets harmless infections pass.

Self-Collection: Breaking Down Barriers to Screening

One of the biggest reasons people skip screening? Discomfort. Fear. Lack of access. Time. Transportation. Shame.

Self-collected HPV testing changes that. You can collect your own sample at home using a simple swab-no speculum, no exam table, no doctor needed. Studies show it’s just as accurate as samples taken in a clinic. Kaiser Permanente began offering it in January 2024. Australia and the Netherlands have rolled it out widely.

In one study, self-collection increased screening rates by 30% to 40% among women who hadn’t been screened in over five years. That’s huge. In the U.S., 30% of cervical cancers occur in women who’ve never had a Pap test. Self-collection could change that.

It’s not yet available everywhere. But it’s coming fast. And it’s a game-changer for rural areas, people with disabilities, and those who’ve had trauma or cultural barriers to pelvic exams.

Why Screening Still Matters Even After Vaccination

A common myth: “I got the vaccine, so I don’t need screening.” That’s dangerous.

The vaccine protects against the most common cancer-causing types-but not all of them. There are over 14 high-risk HPV types. The vaccine covers nine. That’s great, but not complete. Also, not everyone gets all the doses. Not everyone was vaccinated as a teen.

The CDC is clear: vaccinated people need screening the same as unvaccinated people. The vaccine is prevention. Screening is early detection. You need both.

Global Progress-and the Gaps That Still Exist

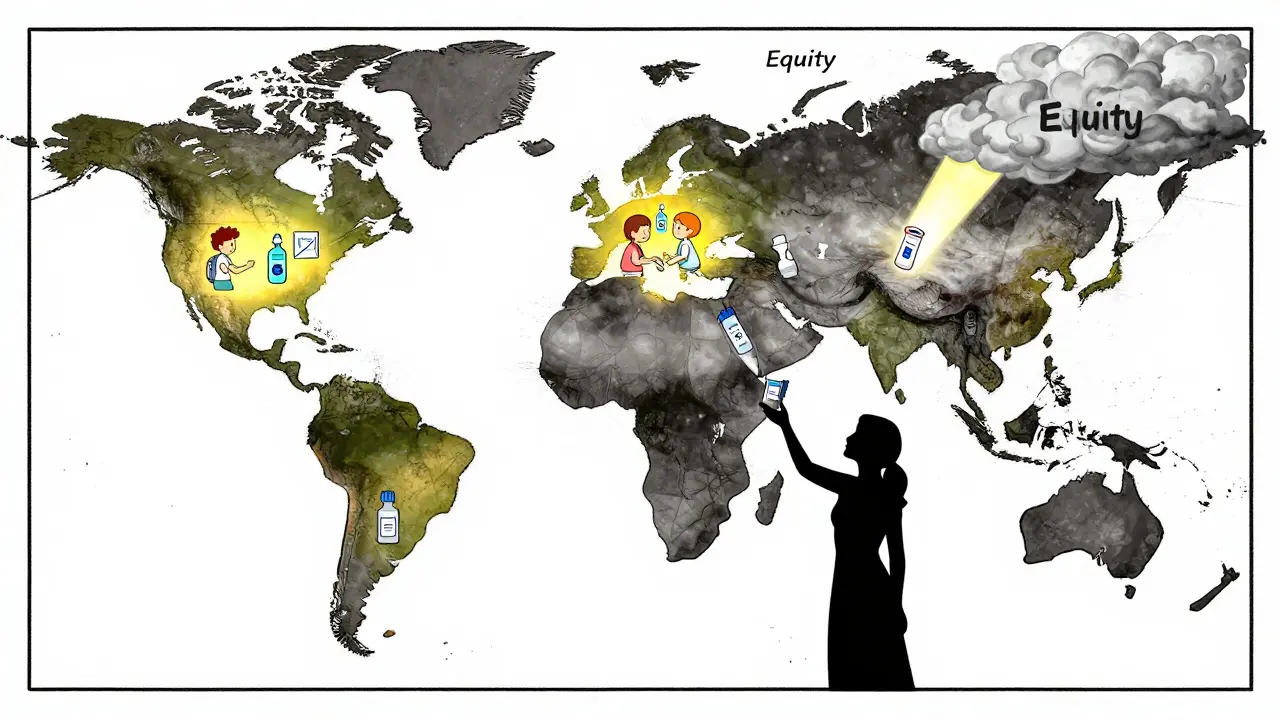

The World Health Organization launched a bold plan in 2020: the 90-70-90 targets by 2030. 90% of girls vaccinated by 15. 70% of women screened by 35 and again by 45. 90% of precancers and cancers treated.

High-income countries are on track. In Australia, cervical cancer could be eliminated by 2035. In the U.S., rates have dropped by 50% since the 1970s thanks to screening.

But globally, the gap is staggering. In low-income countries, only 19% of women have ever been screened. In high-income countries, it’s 80%. Black women in the U.S. die from cervical cancer at 70% higher rates than white women. That’s not biology. That’s access.

Self-collection, mobile clinics, community outreach, and lower-cost tests are the tools to close that gap. The science is ready. What’s missing is equity.

What’s Next? AI, Longer Intervals, and a Cancer-Free Future

The future of screening is smarter and simpler. In January 2023, the FDA approved an AI system called Paige.AI that helps pathologists analyze Pap smears. It doesn’t replace humans-it makes them faster and more accurate.

Research from Wayne State University suggests that after two negative HPV tests, you might be safe for six years-not just five. That’s being studied now. Fewer tests. Less anxiety. Same protection.

By 2025, primary HPV testing will be the dominant method in most high-resource settings. That’s not speculation. It’s what experts like Dr. Mark Schiffman of the NCI are predicting.

And if we hit the WHO targets? Modeling shows we could prevent 62 to 77 million cervical cancer cases over the next century. That’s not a distant dream. It’s a roadmap.

What You Can Do Right Now

- If you’re 25 to 65: Ask your provider about HPV testing every five years. Don’t wait for a Pap test unless you’re under 25.

- If you’re under 26 and haven’t been vaccinated: Get the HPV vaccine. It’s safe, effective, and life-saving.

- If you’re over 26 and never had the vaccine: Talk to your doctor. It’s still beneficial.

- If you’ve avoided screening because of discomfort: Ask about self-collection. It’s available in more places than you think.

- If you’re a parent: Vaccinate your kids at 11 or 12. Don’t wait.

This isn’t about panic. It’s about power. You have tools. You have time. You have choices. Use them.

Is HPV only a women’s issue?

No. HPV affects everyone. In men, it can cause cancers of the throat, anus, and penis. It’s also the main cause of genital warts in both sexes. Vaccinating boys protects them and reduces transmission to future partners. That’s why the vaccine is recommended for all kids, regardless of gender.

Can you get HPV even if you’re in a long-term relationship?

Yes. HPV can stay dormant for years. You might have gotten it decades ago and only now show signs. Or your partner may have had it before you met. It doesn’t mean anyone cheated. HPV is incredibly common-so common that it’s not a sign of behavior. It’s a sign of exposure. Screening and vaccination are the only reliable defenses.

Does the HPV vaccine cause infertility or other serious side effects?

No. Over 15 years of global data show the HPV vaccine is extremely safe. The most common side effects are mild: sore arm, headache, or dizziness. No link has been found to infertility, autoimmune disease, or long-term health problems. The risks of HPV-related cancer far outweigh any known risks from the vaccine.

Why do I need screening if I’ve never had symptoms?

HPV doesn’t cause symptoms until it’s already caused damage. By the time you feel pain, bleeding, or discomfort, it could be too late. That’s why screening exists-to catch changes before they become problems. It’s like checking your blood pressure. You don’t wait until you have a heart attack.

How often do I need to be screened after age 65?

If you’ve had regular screenings with normal results, you can stop at age 65. But if you’ve never been screened, or if you’ve had abnormal results in the past, talk to your doctor. You may still need testing. It’s not about age-it’s about your history.

Is HPV testing covered by insurance?

Yes. Under the Affordable Care Act, HPV screening and vaccination are covered at no cost for most insurance plans in the U.S. Self-collection kits are increasingly covered too. If you’re uninsured, community health centers and state programs often offer free or low-cost testing.

Final Thought: This Is Preventable

Cervical cancer used to be one of the leading causes of death for women. Now, it’s one of the most preventable. We have the vaccines. We have the tests. We have the knowledge. What’s missing is action-consistent, timely, equitable action.

If you’re reading this, you’re already ahead. You’re asking the right questions. Now go get screened. Talk to your doctor. Vaccinate your kids. Share this with someone who needs to hear it. Cervical cancer doesn’t have to be part of anyone’s future.

wendy parrales fong

Just read this and felt so seen. I got my HPV vaccine at 22 because my mom nagged me, and now I’m 30 and so glad I did. No drama, no fear-just peace of mind. Screening’s not scary if you know what’s happening. It’s like getting a car checkup, but for your body.

Also, self-collection? Yes please. I’d do it in my pajamas with a cup of tea.

Jeanette Jeffrey

Oh please. Everyone’s acting like this is some miracle cure. HPV is everywhere. You think a shot stops you from kissing someone or having a partner? Wake up. The real issue is the medical-industrial complex selling fear and vaccines like candy.

And don’t get me started on ‘primary HPV testing’-they just replaced one test with another to keep the labs busy. Pap smears worked fine for decades before corporate medicine ruined everything.

Shreyash Gupta

Bro. I’m from India. My cousin got the vaccine last year. She’s 19. Her mom cried. Said ‘it’s for sluts’. 😔

Meanwhile, my aunt died of cervical cancer at 44. Never screened. Never heard of HPV.

So yeah. Vaccine + screening = life. Not a debate. 🙏

Ellie Stretshberry

i just got my first pap test last year at 28 and honestly i was terrified

but the nurse was so chill and explained everything and it was over in like 2 minutes

now i’m like… why did i wait so long??

also my brother got the vaccine and he said his arm was sore for a day and that was it

Zina Constantin

As someone raised in a culture where women’s health was whispered about, this post changed my life.

I’m 34, never screened, never vaccinated. I’m scheduling my HPV test next week. I’m telling my nieces to get the shot. I’m sharing this with my mom, my sisters, my coworkers.

This isn’t just medicine. It’s liberation.

Thank you for writing this with clarity, not fear.

Dan Alatepe

Y’all actin’ like HPV is some secret club nobody told you about 😭

Girl, I had it at 19. Didn’t know. Didn’t care. Got a Pap. Found something. Got treated. Moved on.

But my cousin? She didn’t go. She died at 32. Left two kids.

So yeah. Get the shot. Get tested. Don’t wait till your body screams.

Life ain’t a Netflix drama. Real consequences. 💔

Angela Spagnolo

I… I didn’t know self-collection was a thing…

I’ve avoided screening for 8 years because… I just… I couldn’t face it.

But now that I know I can do it at home… I think… maybe… I’ll try it…

Thank you for saying that out loud.

It feels… less scary now.

…I’m calling my doctor tomorrow.

…I promise.

Sarah Holmes

This is a dangerous piece of propaganda. You are normalizing a vaccine that has been linked to neurological damage, autoimmune disorders, and premature ovarian failure. The data you cite is funded by Big Pharma. You are manipulating vulnerable women into believing they are powerless without corporate intervention. This is not prevention-it is control.

Where are the long-term studies? Where is the transparency? You dismiss dissent as ignorance, but I am not ignorant-I am vigilant.

Jay Ara

my sis got the shot at 14 now she’s 20 and healthy

my mom said it was for boys only

turns out it’s for everyone

screening is free at my local clinic

just go

you got this

Michael Bond

Vaccine works. Screening saves lives. Self-collection is the future. Done.