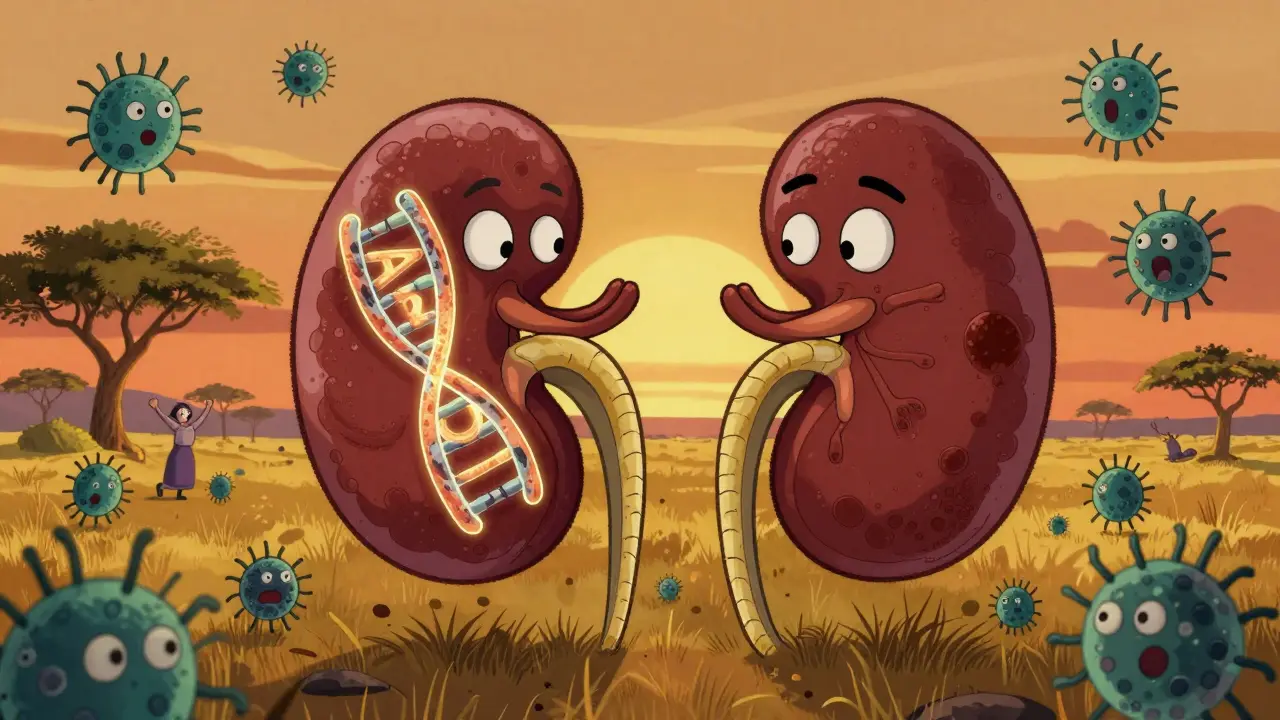

For people with recent African ancestry, kidney disease isn’t just about high blood pressure or diabetes. A hidden genetic factor is quietly shaping who gets sick and who doesn’t-and it’s not race. It’s ancestry. The APOL1 gene carries variants that evolved to protect against a deadly parasite, but today, they’re linked to a higher risk of kidney failure. This isn’t a theory. It’s science backed by decades of research, and it’s changing how we understand kidney health in millions of people around the world.

What Is the APOL1 Gene, and Why Does It Matter?

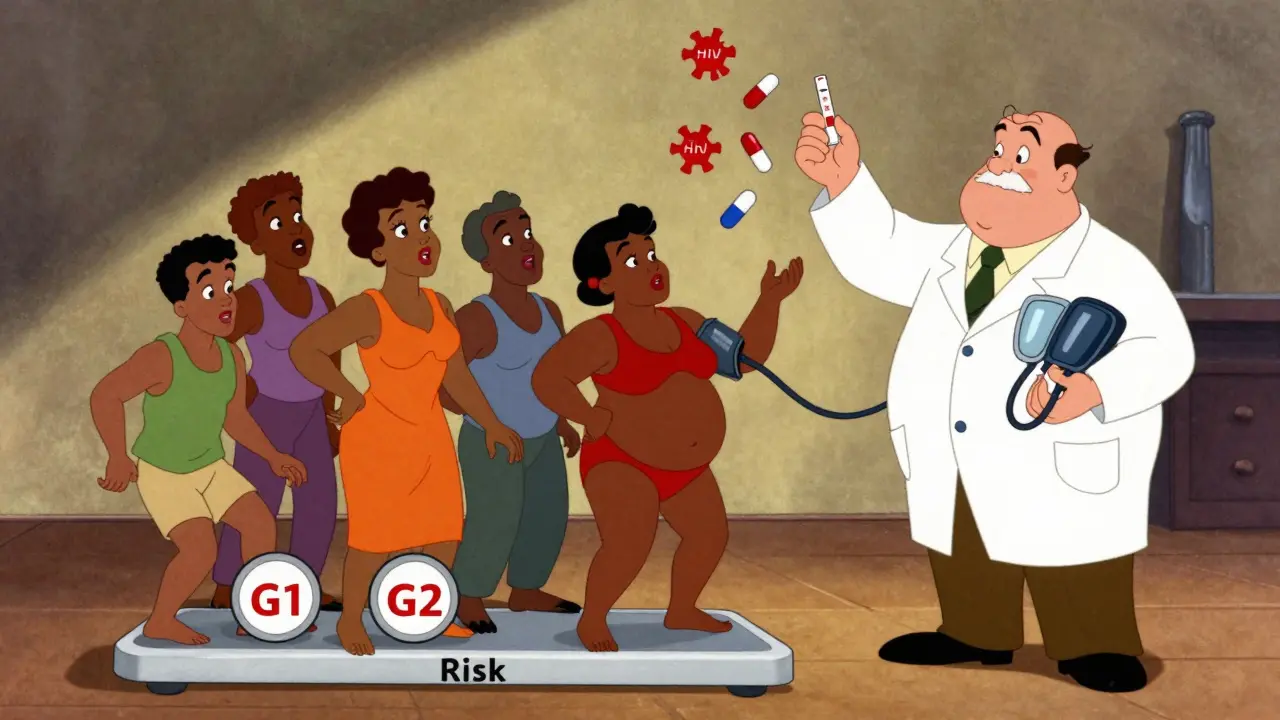

The APOL1 gene makes a protein that helps your immune system fight off certain parasites. Around 3,000 to 10,000 years ago, in West and Central Africa, a version of this gene changed slightly. These changes-called G1 and G2 variants-made the protein better at killing the Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense parasite, which causes African sleeping sickness. That gave people with these variants a survival edge. Over generations, the variants became common in populations from that region.

But here’s the twist: the same changes that saved lives from parasites now raise the risk of kidney damage. The APOL1 protein, in its mutated form, doesn’t just attack parasites. It can also harm kidney cells. This isn’t a mistake in evolution-it’s a trade-off. Protection from a deadly infection came at the cost of increased vulnerability to chronic disease later in life.

Today, about 30% of people with West African ancestry carry at least one of these variants. But having one copy isn’t enough to cause trouble. You need two-either two G1s, two G2s, or one of each (called compound heterozygosity). Only then do you fall into the high-risk category. That’s about 13% of African Americans, and even higher among those already diagnosed with non-diabetic kidney disease.

Who Is Affected-and Who Isn’t?

This isn’t a global issue. The high-risk APOL1 variants are almost never found in people of European, Asian, or Indigenous American ancestry. That’s why the massive gap in kidney failure rates between African Americans and white Americans exists. African Americans are 3 to 4 times more likely to develop kidney failure. APOL1 explains about 70% of that difference.

But here’s something many don’t realize: most people with high-risk APOL1 genotypes never develop kidney disease. Around 80 to 85% of them keep healthy kidneys their whole lives. That’s called incomplete penetrance. It means having the gene doesn’t equal a diagnosis. Something else has to trigger it-a “second hit.” That could be HIV, obesity, uncontrolled high blood pressure, or even certain medications. That’s why a person with APOL1 risk might stay healthy until they get sick with an infection or gain weight.

Studies show that among African Americans with HIV, nearly half of all end-stage kidney disease cases are tied to APOL1. The same is true for certain rare but aggressive forms of kidney disease like collapsing glomerulopathy and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). In fact, up to 50% of African Americans with non-diabetic kidney disease carry two high-risk APOL1 variants.

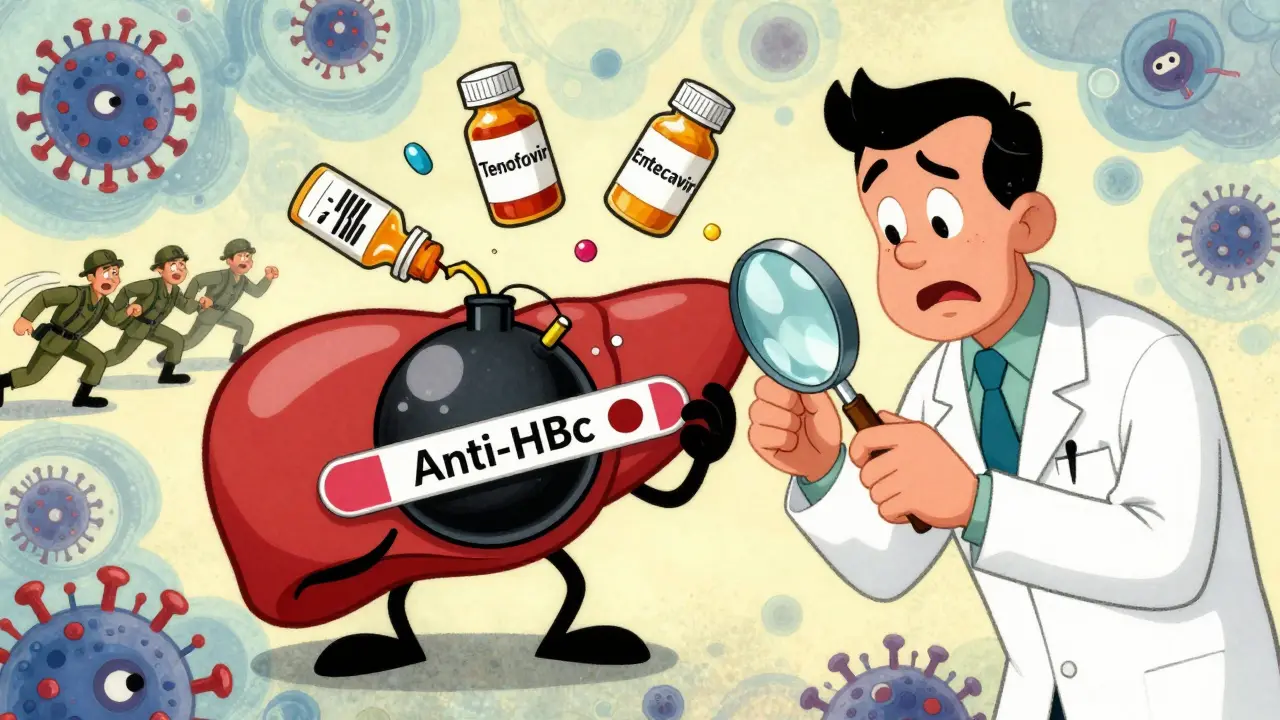

Testing for APOL1: Who Should Get It?

APOL1 testing became available in 2016. It’s a simple blood or saliva test that looks for the G1 and G2 variants. The cost ranges from $250 to $450 without insurance. Some insurance plans cover it if you have kidney disease or are being evaluated as a living kidney donor.

Right now, the strongest reason to test is if you’re considering donating a kidney. If you have African ancestry, knowing your APOL1 status helps doctors decide if donating is safe for you. Donating a kidney when you carry two high-risk variants could put your own kidney health at risk later.

For people already diagnosed with kidney disease, testing can help explain why it happened-especially if there’s no clear cause like diabetes or high blood pressure. For others, the decision is trickier. Some people want to know to take action early. Others worry about anxiety or discrimination.

A 2022 survey of nephrologists found that 78% felt unprepared to explain APOL1 results to patients. Many patients misunderstand the risk. One patient thought a positive test meant they’d definitely get kidney failure. In reality, the chance is about 1 in 5 over their lifetime. That’s serious-but not certain.

What Can You Do If You Have High-Risk APOL1?

If you’ve tested positive for two high-risk variants, you can’t change your genes. But you can change your habits. The American Society of Nephrology recommends three key steps:

- Keep your blood pressure under 130/80 mmHg. Use home monitoring and work with your doctor on the right meds.

- Get a yearly urine test for albumin (albumin-to-creatinine ratio). This catches early kidney damage before it’s obvious.

- Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen. These drugs can stress kidneys, especially in APOL1 carriers.

Weight management, quitting smoking, and controlling blood sugar (even if you’re not diabetic) also help. One woman, Emani, found out she had high-risk APOL1 before any kidney damage. She started checking her urine yearly, lost 20 pounds, and kept her kidney function stable for over five years. That’s the power of early awareness.

Why This Isn’t About Race

It’s easy to hear “African ancestry” and think “race.” But race is a social idea. APOL1 is biological. It’s about where your ancestors lived-and the diseases they faced.

Dr. Olugbenga Gbadegesin, a pediatric nephrologist, warns that using race to estimate kidney function (like the old race-adjusted eGFR formula) is misleading. That formula assumed Black people naturally had higher kidney function. But it wasn’t race-it was APOL1. That’s why the American Medical Association and others now recommend dropping race from kidney function calculations. We need to measure genes, not skin color.

This distinction matters. A person with West African ancestry who grew up in Sweden still carries the same genetic risk. A person with no African ancestry, even if they identify as Black, doesn’t have it. APOL1 isn’t about identity. It’s about DNA.

New Treatments on the Horizon

For years, doctors could only manage symptoms. Now, real treatments are coming. Vertex Pharmaceuticals is developing a drug called VX-147, designed to block the harmful effects of the APOL1 protein. In a 2023 trial, it reduced protein in the urine by 37% in just 13 weeks-something no current kidney drug has done so quickly.

The NIH has invested $125 million in APOL1 research since 2020. A new 10-year study, the APOL1 Observational Study, is tracking 5,000 people with high-risk genotypes to find out what triggers kidney damage and how to stop it.

If these drugs work, they could cut kidney failure rates in high-risk groups by 25 to 35% by 2035. But there’s a catch: access. Right now, only 12% of low- and middle-income countries can test for APOL1. If these drugs become available, will they reach the people who need them most? That’s the next big challenge.

What’s Next for APOL1 Research?

Scientists are working on three big goals by 2027:

- Building better tools to predict who will develop kidney disease (not just who has the gene)

- Creating official screening guidelines for high-risk groups

- Making testing affordable and available everywhere, not just in wealthy countries

One day, we might screen newborns with African ancestry for APOL1, just like we do for sickle cell. That way, people can start protective habits early-before any damage happens.

But for now, the message is simple: if you have African ancestry and you’re worried about your kidneys, ask about APOL1. Get your blood pressure checked. Get your urine tested. Know your risk-not because you’re doomed, but because you can act.

What does it mean to have two APOL1 risk variants?

Having two APOL1 risk variants (G1/G1, G2/G2, or G1/G2) means you carry a genetic profile linked to a higher chance of developing certain types of kidney disease. But it doesn’t mean you will definitely get sick. About 80-85% of people with this genotype never develop kidney failure. The risk becomes real only when other factors-like HIV, obesity, or uncontrolled high blood pressure-act as triggers.

Can I get tested for APOL1 if I don’t have kidney disease?

Yes, but it’s not routinely recommended for everyone. Testing is most useful if you’re being evaluated as a living kidney donor, have unexplained kidney disease, or want to take proactive steps to protect your kidneys. If you’re healthy and have no symptoms, discuss the pros and cons with a doctor or genetic counselor. The emotional impact of knowing your risk can be significant, so it’s important to be prepared.

Is APOL1 testing covered by insurance?

Sometimes. Insurance is more likely to cover APOL1 testing if you’re being evaluated as a living kidney donor or have already been diagnosed with non-diabetic kidney disease. For healthy individuals, coverage is less common. The test typically costs $250-$450 out-of-pocket. Some labs offer payment plans or financial aid through nonprofit programs like the American Kidney Fund.

Does APOL1 affect kidney transplant outcomes?

Yes. People with high-risk APOL1 genotypes who receive a kidney transplant from a donor without these variants generally do well. But if the donor has two high-risk variants, the transplanted kidney is more likely to fail early. That’s why living donors with African ancestry are now routinely tested for APOL1 before donation. It protects both the donor and the recipient.

Why aren’t all Black people at risk for APOL1-related kidney disease?

Not all Black people have African ancestry from West or Central Africa, where the APOL1 variants originated. People with ancestry from East Africa, the Caribbean, or the Americas may have different genetic backgrounds. Also, even among those with West African ancestry, only about 13% carry two high-risk variants. So while the risk is higher in this group, it’s not universal. Genetics, not race, determines the risk.

If you have African ancestry and are concerned about your kidney health, talk to your doctor about APOL1. Know your numbers. Monitor your blood pressure. Get your urine checked. You can’t change your genes-but you can change your future.

Mindee Coulter

Finally someone breaks this down without using race as a proxy. I work in public health and this is exactly the kind of science we need to center-genes, not skin color. I’ve seen too many patients get dismissed because their eGFR was ‘normal’ based on outdated race adjustments.

Colin Pierce

My uncle got diagnosed with FSGS at 42-no diabetes, no hypertension. Turns out he had two APOL1 risk variants. He’s been on ACE inhibitors since, monitors his urine every 6 months, and avoids NSAIDs like the plague. He’s still got 85% kidney function at 51. Knowledge saved his kidneys.

Anna Lou Chen

Let’s not romanticize evolutionary trade-offs as some noble sacrifice. The APOL1 variant didn’t ‘evolve’-it was selected under brutal, colonial-era parasitic pressure. Now we’re weaponizing this genetic legacy to justify medical neglect in Black communities. The real tragedy isn’t the gene-it’s the system that ignores it until someone’s on dialysis. And don’t get me started on Vertex’s $100K/year drug that’ll be inaccessible to 95% of the people who need it.

This isn’t science. It’s biopiracy with a side of performative empathy.

Rhiannon Bosse

Wait-so you’re telling me the same gene that protected Africans from sleeping sickness is now ‘causing’ kidney disease? But why hasn’t Big Pharma tried to ‘fix’ this before? Hmm… maybe because they’ve been profiting off dialysis machines and transplant meds for decades? And now they’ve got a shiny new drug to sell? Classic. They’ll charge $120K a year and call it ‘precision medicine’ while Medicaid denies coverage. Don’t be fooled. This isn’t progress-it’s profit repackaged as science.

Lexi Karuzis

...I knew it. I KNEW IT. This is why they push genetic testing only for donors-not for patients. It’s a trap. They want you to think you’re in control, but really they’re just trying to offload liability. If you test positive and get kidney disease, it’s ‘your genes,’ not their negligence. If you don’t test, and you get sick, it’s ‘your fault for not knowing.’ Either way, they win. And don’t even get me started on how they’re using this to justify cutting Medicaid coverage for ‘high-risk’ people under ‘preventive care’ loopholes. They’re building a eugenics pipeline with lab coats.

Brittany Fiddes

Frankly, I’m shocked this isn’t front-page news in every UK newspaper. We’ve got a genetic variant that explains 70% of a health disparity-and we’re still using race-adjusted eGFR in NHS clinics? This is scientific illiteracy dressed as policy. And don’t even get me started on how the US is letting pharmaceutical companies monetize ancestral trauma. If this were a European population, we’d have universal screening by now. But no-because it’s Black people, we delay, debate, and monetize.

It’s not science. It’s colonialism with a CRISPR twist.

SRI GUNTORO

So you’re saying it’s okay to test people for this gene but not offer them affordable treatment? That’s not prevention-that’s cruelty disguised as awareness. People with this variant should be getting free screenings, free meds, free nutrition counseling. Instead, we tell them to ‘watch their blood pressure’ while food deserts and Medicaid cuts make that impossible. This isn’t science. It’s moral failure with a lab report.

John Rose

My sister is a nephrologist in Atlanta. She told me about a 28-year-old patient who came in with massive proteinuria-no diabetes, no hypertension. Tested positive for two APOL1 variants. Started on SGLT2 inhibitor, lost 15 lbs, stopped ibuprofen, and now her ACR is normal. She’s back to teaching kindergarten. This isn’t doom. It’s a call to action. If you have African ancestry, ask your doctor about APOL1. Not because you’re scared-but because you deserve to know.