Quick Take

- Skin chafe starts with friction that breaks down the outer skin layer.

- Moisture and sweat amplify damage by weakening the skin barrier.

- Inflammatory responses cause redness, pain, and sometimes infection.

- Choosing the right fabrics, staying dry, and using protective creams can stop the cycle.

- Treat chafed skin promptly with gentle cleaning, soothing balms, and breathable clothing.

Skin chafe is a mechanical irritation of the skin caused by repeated friction, moisture, and shear forces, often seen where skin rubs against skin or clothing. The sensation ranges from mild tingle to painful rawness, and if ignored it can turn into a chronic irritation.

Understanding why chafe occurs isn’t just academic - it tells you exactly how to stop it before it becomes a full‑blown sore. Below we break the process down into four layers: friction, the skin’s protective barrier, the body’s inflammatory reaction, and the practical ways to intervene.

The Role of Friction

Friction is a force that opposes motion between two surfaces. When you jog, hike, or simply walk, skin slides against fabric or another patch of skin, generating a friction coefficient that can range from 0.2 (smooth silk) to 0.8 (rough denim). The higher the coefficient, the more kinetic energy is converted into heat and shear stress on the outer skin layer.

Scientists measure friction with a tribometer, a device that records the force needed to pull a fabric strip across a skin‑like polymer. In a 2023 dermatology lab, cotton T‑shirts averaged a friction coefficient of 0.35, while synthetic polyester blends hit 0.48 - a clear reason why athletes often switch to technical fabrics.

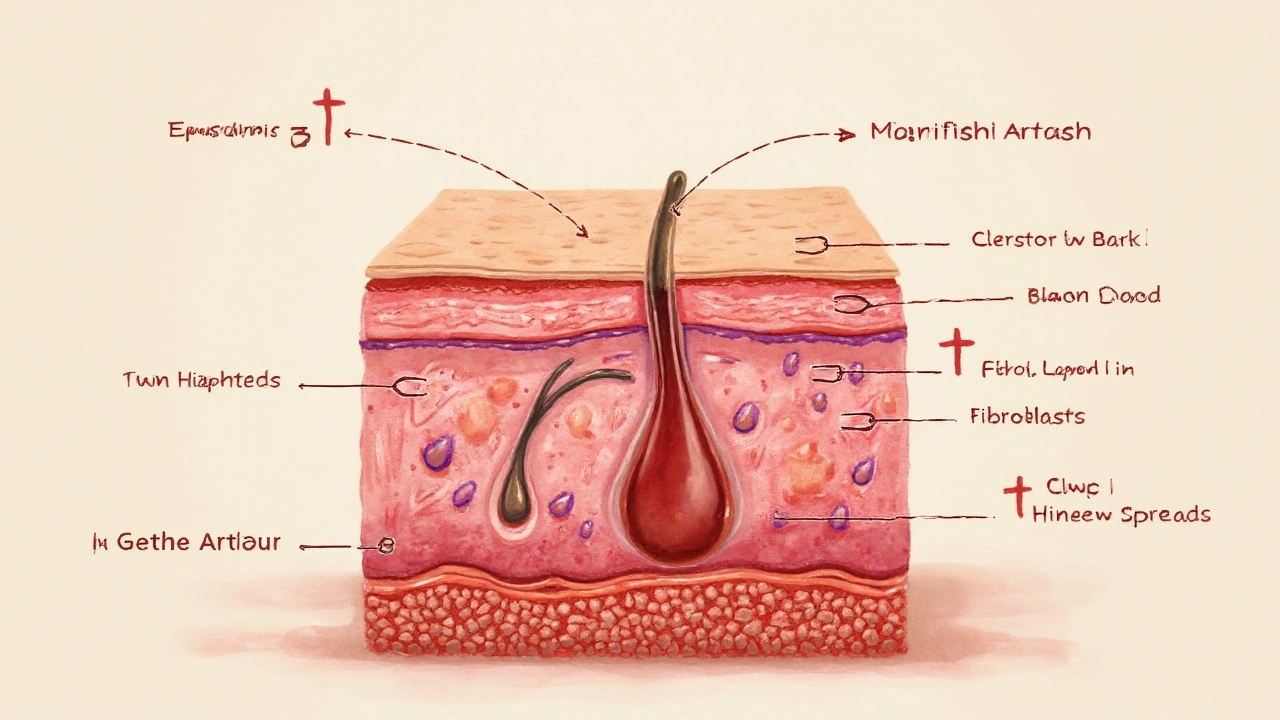

Skin’s First Line of Defense - The Epidermis

Epidermis is a thin, outermost layer of skin composed mainly of keratinocytes. Within the epidermis, the stratum corneum acts like a brick‑and‑mortar wall: dead, flattened cells (bricks) are packed together by lipid “mortar” that retains moisture and blocks irritants.

When friction repeatedly scrapes the stratum corneum, the lipid mortar cracks, and the bricks start to slough off. This loss is quantified as transepidermal water loss (TEWL), measured in g/m²/h. Healthy skin typically shows TEWL of 5-10g/m²/h; chafed skin can spike above 30g/m²/h, indicating a compromised barrier.

Moisture - The Silent Aggravator

Sweat sounds harmless, but it’s a double‑edged sword. Sweat contains salts, urea, and lactic acid, all of which act as chemical irritants once they seep into micro‑tears. Moreover, moisture softens the stratum corneum, lowering its elastic modulus by up to 40% in lab tests, which makes it easier for friction to pull cells apart.

Studies from the Australian Institute of Sports (2022) showed that runners who wore moisture‑wicking leggings experienced 55% less chafing than those in cotton shorts, underscoring the importance of keeping the skin dry.

Inflammation - Your Body’s Alarm System

When the skin barrier breaks, immune cells rush in. Inflammation is a complex vascular response that brings white blood cells, cytokines, and heat to the affected area. The visible signs - redness (rubor), swelling (tumor), and pain (dolor) - are the classic “four signs” described by ancient physicians.

Key mediators include histamine, prostaglandin E₂, and interleukin‑1β. Their combined effect increases blood flow, which you feel as a warm, uncomfortable sting. If the chafed area stays moist, bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus can colonize the wound, turning a simple irritation into an infection.

Preventive Strategies - Break the Cycle

Now that we know the science, let’s translate it into everyday actions. The table below compares three common mitigation methods.

| Method | Friction Reduction | Moisture Management | Barrier Strengthening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical fabrics (polyester‑spandex blend) | Low (0.30‑0.35) | High - wicks sweat away | Moderate - smooth surface |

| Powdered talc or anti‑chafe powders | Very low (lubricates surface) | Medium - absorbs moisture | Low - does not repair skin |

| Barrier creams (zinc oxide, dimethicone) | Medium - creates film | Medium - repels water | High - restores lipid layer |

Pick the option that fits your activity. Long‑distance runners swear by technical tights, while hikers often pair talc with a breathable shirt. For anyone with sensitive skin, a thin layer of zinc‑oxide cream before dressing forms a protective shield without feeling greasy.

Step‑by‑Step Treatment Plan

- Clean gently. Rinse the area with lukewarm water and a mild, fragrance‑free cleanser. Avoid scrubbing - you’ll only worsen the micro‑tears.

- Pat dry. Use a clean, soft towel. Leaving the skin slightly damp helps barrier creams absorb better.

- Apply a soothing barrier. Look for products with dimethicone (a silicone that forms a breathable film) or zinc oxide. A pea‑sized amount spreads evenly over the chafed patch.

- Dress smart. Opt for seamless, low‑friction fabrics. If you must wear cotton, add a thin, polyester liner to reduce direct contact.

- Monitor for infection. Redness that spreads, increasing pain, or pus formation signals bacterial involvement. In that case, see a health professional for topical antibiotics.

Following these steps usually resolves mild chafing within 2-3 days. More severe cases may need a short course of oral anti‑inflammatories, but that’s a decision best left to a doctor.

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Skin chafe is closely linked to other dermatological topics you might explore next:

- Heat rash - irritation caused by blocked sweat ducts.

- Contact dermatitis - allergic reaction to fabrics or detergents.

- Fungal intertrigo - infection that thrives in warm, moist skin folds.

Each of these conditions shares the same underlying theme: a compromised skin barrier. Strengthening that barrier with proper moisturization, nutrition (vitaminE, omega‑3 fatty acids), and skin‑friendly clothing creates a long‑term defense against many irritations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does chafing hurt more when I’m sweating?

Sweat softens the stratum corneum and adds salt crystals that act like tiny abrasives. The combination of a weakened barrier and increased friction makes the nerves fire more intensely, so the pain feels amplified.

Can I use regular body lotion to prevent chafing?

Most everyday lotions are designed to moisturize, not to create a low‑friction surface. They can become sticky when mixed with sweat, actually increasing friction. Look for products labeled “anti‑chafe,” “sport balm,” or those containing dimethicone or zinc oxide.

Is chafing the same as a friction burn?

They’re related but not identical. A friction burn involves enough heat to actually scorch the skin, often leaving a blister. Chafing is primarily mechanical irritation that may or may not generate noticeable heat.

How long does it take for a chafed area to heal?

Mild cases usually heal in 2‑3 days with proper care. Moderate irritation can take up to a week. If the skin stays red, painful, or starts oozing after 5 days, see a clinician.

Can diet influence my skin’s resistance to chafing?

Yes. A diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids (found in fish, flaxseed, walnuts) supports lipid production in the stratum corneum, improving barrier function. VitaminE and zinc also help skin repair and reduce inflammation.

Should I keep chafed skin exposed or covered?

If the area is clean and you’ve applied a barrier cream, keeping it uncovered promotes airflow and speeds drying. However, during active movement, a breathable, low‑friction covering prevents new friction.

Liam Mahoney

Honestly, if you keep letting your skin chafe without a care, you're basically inviting infection. It's not just a tiny irritation, it's a full blown breach in your barrier. Stop being lazy and get the right fabrics, or you'll end up with a mess.

Justin Ornellas

One cannot simply dismiss the intricate ballet of friction, moisture, and inflammatory cascades as "just chafing." The literature is replete with studies illustrating how a compromised stratum corneum precipitates a cascade of cytokine release, thereby amplifying nociception. In short, proper attire and barrier creams are not optional-they are essential safeguards against dermatological disaster.

JOJO Yang

Okay, listen up-if you think a little rub will hurt you later, think again! The skin loosens up like a bad drama, and before you know it you're swimming in pain. Get yourself some anti‑chafe powder, or else you'll be begging for mercy.

Faith Leach

What they don't tell you is that the elite are pumping chemicals into everyday fabrics to keep us dependent on their proprietary creams. The real cure is staying off the grid, wearing raw natural fibers, and refusing the corporate gimmicks. Wake up!

Eric Appiah Tano

Hey folks! Great post-just wanted to add that I've seen runners swear by bamboo blend tights for a reason. They wick moisture like a champ and feel super soft on the skin, cutting down friction dramatically. Give it a try and let us know how it works for you!

Jonathan Lindsey

The epidermal barrier, when compromised by repetitive shear, initiates a cascade that is both biomechanical and immunological.

First, the stratum corneum's lipid matrix loses cohesion, allowing transepidermal water loss to surge beyond physiological norms.

Such a surge is measurable; values exceeding thirty grams per square meter per hour signal a breach that warrants immediate attention.

Concurrently, mechanoreceptors embedded in the epidermis transmit amplified nociceptive signals, which our brain interprets as sharp discomfort.

The vascular response follows, delivering histamine and prostaglandin E₂ to the site, thereby increasing local perfusion and redness.

These mediators also promote the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages, whose purpose is to clear debris but can exacerbate inflammation if unchecked.

In the presence of moisture, the situation deteriorates further, as sweat constituents act as chemical irritants that lower the elastic modulus of the skin.

Laboratory studies have demonstrated a forty‑percent reduction in modulus when keratinocytes are bathed in a saline solution mimicking sweat.

This softening effect reduces the skin's ability to resist shear, creating a feedback loop where friction begets more friction.

From a materials science perspective, the coefficient of friction for synthetic fibers remains lower than that of cotton, explaining the observed disparity in chafing incidence among athletes.

Moreover, the thermodynamic heat generated by friction raises local temperature, which can further increase enzymatic activity contributing to tissue breakdown.

If bacterial colonization occurs, Staphylococcus aureus secretes proteases that degrade extracellular matrix components, turning a simple abrasion into a potential infection.

Clinical guidelines therefore recommend not only mechanical mitigation but also antimicrobial vigilance, especially in humid environments.

Applying a dimethicone‑based barrier cream restores a synthetic lipid layer, effectively reducing TEWL and shielding the skin from external irritants.

In practice, a thin film of zinc oxide can serve a dual purpose: it offers UV protection and provides a physical barricade against friction.

Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach-combining appropriate apparel, diligent hygiene, and targeted topical agents-optimizes recovery and prevents recurrence.

Gary Giang

I’ve been coaching a trekking group for years, and the consensus is that breathable, seamless fabrics make the biggest difference. Pair them with a light powder and you’ll hardly notice any friction. Stay safe out there.

steve wowiling

From a philosophical standpoint, the skin is merely a canvas upon which friction paints its story-sometimes a masterpiece, often a mess. If you treat it with respect, the narrative stays smooth.

Warren Workman

While the prevailing consensus champions synthetic blends, one must consider the viscoelastic shear‑thinning properties of traditional wool, which paradoxically reduce peak friction under high‑strain conditions. The narrative is not as binary as mainstream marketing suggests.

Kate Babasa

Interesting point!; however, let's not overlook that individual skin pH can also influence the efficacy of barrier creams. ; Therefore, testing a small area first is wise; it ensures compatibility and prevents unexpected reactions.

king singh

Use a good anti‑chafe stick and stay dry.

Adam Martin

Seriously, that one‑liner hits the nail on the head. I’ve found that a dab of petroleum jelly before a long run can make the difference between a smooth jog and a painful finish line. It’s a simple hack that works wonders.

Ryan Torres

Yo, chafing is basically your skin screaming for help 😱. Keep it dry, slap on some zinc oxide, and you’ll be good. Trust the process! 🚀

shashi Shekhar

Sure, because we all love slapping greasy stuff on our bodies and hoping for the best. Maybe try a breathable fabric before you start the whole “apply everything” routine?

Marcia Bailey

Great summary! 😊 For anyone dealing with chafed skin, I recommend a gentle, fragrance‑free cleanser and then a thin layer of Aquaphor. It’s soothing and helps restore the barrier quickly.

Hannah Tran

Thanks for the tip! Adding a ceramide‑rich moisturizer can also replenish the lipid matrix, enhancing barrier repair while keeping the area breathable. Consistency is key for lasting relief.

Crystle Imrie

Chafing isn’t just a nuisance-it’s a preventable condition when you respect the science.

L Taylor

True, and the data speaks for itself but we can keep it simple and just say wear the right gear

Matt Thomas

Listen up, folks-if you keep wearin cottons you’ll jus end up with a damn rash. Get proper sports gear or suffer the consequence.

Nancy Chen

While the aggressiveness of cotton can be a real pain, swapping to a vibrant, moisture‑wicking blend not only mitigates chafing but also adds a splash of color to your workout wardrobe-making the whole experience both functional and fun.